Could a robot ever replace a human bush carer?

It is a question which has nagged at me for more than 25 years – since I first started doing volunteer bush care work – and, according to the experts, the answer now appears to be a cautious ‘yes’.

For those who don’t know what a bush carer does, the work mostly consists of restoring native vegetation by removing invasive weeds.

For those who don’t know what a bush carer does, the work mostly consists of restoring native vegetation by removing invasive weeds.

Mostly such weeding is done manually – hand pulling, or grubbing out with various tools, or dosing the leaves or stems of weeds with herbicide. The aim is always to avoid ‘off target’ damage to native plants, and to minimise disturbance to the bush.

More often than not, bush carers work under a tree canopy in dense vegetation, and frequently on challenging terrain (slopes, rocks, gullies). And typically bush carers need to return to the same sites numerous times over many years, until the weed seedbed is spent.

All that adds up to a lot of labour-intensive work.

And how big a problem are invasive bushland weeds? How many thousands of hectares – indeed, how many thousands of square kilometres – are in desperate need of weeding? No-one really knows, except that it is a huge problem.

According to Australia’s Invasive Species Council (ISC), almost half of NSW’s threatened species, and most of its endangered ecological communities, are threatened by weed invasion.

“Weeds can be as destructive as land clearing – displacing and threatening native species and transforming ecosystems,” the ISC says on its website.

Australia has a lot of bush care volunteers. Tens of thousands, probably. And we have a similarly large paid bush regeneration workforce. As one of the volunteers, who has worked with many of the professionals, I am in awe of what this combined professional and volunteer workforce can achieve.

But I am also worried about the future. The scale of the problem is so huge, and so long-term, and the capacity of both volunteers and professionals is so stretched, that it seems unimaginable such a concerted effort can be maintained over generations to come. Which it will need to be, especially as climate change does its deadly mischief to our ecosystems.

My fantasy solution is this: a cheap, renewably-powered robot that could patrol an uneven bushland site, identify invasive weeds and inject them with herbicide – all without damaging the surrounding vegetation.

If you talk to the experts, it turns out this fantasy may not be so far away.

‘It’s definitely coming’, say the experts

Andrew Davies is the CEO of Taz Drone Solutions, which – among other things – employs drones to spot spray weeds in difficult locations, most notably on cliffs and dam walls under contract to Hydro Tasmania. Davies keeps a close eye on the new technologies now emerging around the world.

“There’s so much emerging,” he says. “It’s definitely coming, the question is, is it going to be in time. But I definitely think it’s possible.”

Eureka Prize winner Professor Salah Sukkarieh, from the University of Sydney, is one of Australia’s leading developers of robots for agriculture – including SwagBot, which can navigate open pasture, identifying and treating weeds such as serrated tussock and African box thorn.

Professor Sukkarieh says developing a bushcare robot is “very plausible”, although it would require a funded research program to overcome the challenges presented by the terrain.

“There are terrains and there are terrains,” he says. “It comes down to the complexity – and you can always design the robotic platform to deal with any type of terrain, but then the cost and maintenance increases.”

Professor Sukkarieh says the existing SwagBot platform can already deal with 15-degree slopes and ditches 50-100 centimetres deep, and that a more important research problem for a bush care robot would be its ‘perception’ system – the sensors and algorithms it would need to understand the terrain.

“Can it see the ditches, and avoid the logs? Can it navigate around trees. What if the ditch is covered with pasture? What if there are a collection of trees and logs that make it untraversable – will it know this before it sets out?”

“The perception problem is always the work that is being focussed on in R&D and that changes with changing terrain types. And you don’t want to spend a lot of money on complex sensors.”

A bush care robot could not rely on GPS, he says, because of the tree foliage – so sensors were all-important.

“Taking SwagBot into a bush care activity would be an easy application transfer, but would require funding to solve specific elements in bush care.”

“It would be a mixture of an ag robot in versatility with a space robot in terms of requiring autonomy for long durations without comms and human interaction – a challenge but not something that would be impossible, in fact very plausible, but needs the funding to focus on it.”

‘For bush care it could be 10-15 years’

Davies’ Taz Drone devices are operator controlled – they don’t have an on-board AI to seek out and treat weeds. But he says the onboard computer power and problem-solving capacity is increasing all the time, and numerous innovative approaches to weed control are being tested world-wide.

In the rapidly evolving field of agricultural robotics, numerous technologies are being commercialised around the world for weed control – including micro-herbicide injections, lasers, electric shocks and mechanical devices. Davies mentions a Chinese-developed agricultural weed robot, which carries thousands of small “guns” which shoot fine bursts of herbicide at emerging weeds in crops.

“There’s no reason that this can’t be integrated into something that’s flying,” he says. “Even if it’s a swarm of small drones flying in under the canopy. If you’ve got a thousand drones carrying a few grams each…”.

Davies says drone technology is now used for weeding only in niche areas, where access is difficult for humans – such as on cliff faces, or in estuarine areas where the vagaries of tides mean weeding crews working in the water, sometimes in the dark.

“We’ve got a really big rice grass problem here on the Rubicon in North West Tasmania. I reckon it’s a perfect job for the drones. It’s just a shit place for people to be.”

How many years into the future are we talking about? Professor Sukkarieh says the answer is largely a question of how much money is invested in developing the necessary technology.

“In agriculture we generally are about 10 years behind what you see in mining and defence robotics,” he says.

“So if you see a robot out there operating in your environment run by mining/defence company, then that technology will probably be available to the agriculture community in 5-15 years.”

“For bush care it could be more like 10-15 years. It comes down to bringing the cost of the technology down – which comes with time – and having enough people interested in solving the problem for bush care, which requires funding.”

The cost to develop a bush care robot, Professor Sukkarieh estimates, would be “in the order of hundreds of thousands, and then into a couple of million to have a commercial system”. The target would be to develop a robot which would cost roughly the same as an ATV (all-terrain-vehicle).

Why bother?

As I said, I am a volunteer bush carer. You get to do a lot of thinking while you are crouched in the bush with a pair of secateurs and a swab bottle.

Bush care is not a dangerous task – although in the Adelaide Hills you do have to keep a wary eye out for the local Myrmecia species (hoppers and inch ants) – but it can be irksome.

Particularly in hot or wet weather. Particularly if you are re-visiting an area you have already weeded several times before. Particularly if the weedlings are depressingly numerous. Particularly if you are getting on in years, and no younger volunteers are lining up to succeed you.

I am now in my 60s, and I am one of the youngest regular bush care volunteers in our group. I understand why new volunteers are hard to find – people who live nearby and who have an interest in conservation already have a lot to do on their own properties.

While I am crouched in the bush, I sometimes like to imagine myself as being akin to one of those legendary European medieval monks – the scribes who copied ancient texts onto new vellum every few generations, so that the wisdom of the past could be preserved for the future, even if no-one at the time was interested.

Just as generations of anonymous monks carried the light of learning through a time of ignorance into a grateful future, I imagine, so might a generation of anonymous bush carers carry patches of intact ecosystems through Australia’s environmental dark age into a future which values those patches, and has the resources to re-build from them.

But like the sputtering candles of those monks, I fear that the light of many bush care groups might also be slowly going out – as we age, and as we face the reality that in the end we aren’t actually monks, and that maybe replacing us with automata is a more reliable bridge to the future.

I also think robots might end up being better than humans at bush care weeding – at least with the more common weeds which make up the bulk of the task.

Mostly bush care involves dealing with large numbers of the same weeds – I would guess about 25 species on the sites I work on. The rule is, anything you are not sure about, you leave.

So on a typical terrestrial remnant bushland site, a robot might need to identify and treat (say) about 100 species of weeds accurately to do most of the work of a human bush carer. And it could stay out there all day doing it.

In 2016 a prototype submarine robot called COTSbot made headlines. Developed by the Queensland University of Technology, COTSbot detects crown of thorns starfish growing on the Great Barrier Reef, and injects them with a biocide. Armed with machine learning, COTSbot now claims to have a 99% accuracy at recognising pest starfish.

That sort of accuracy is better than most humans can achieve.

I suspect there will always be a place for professional bush regenerators, and perhaps for skilled bush care volunteers. After all, someone will still have to assess and review the sites, watch out for unusual or emerging weeds, and to carry out some of the other tasks which go with managing bushland. Someone will still have to go to all the meetings, puzzle over disputed taxonomy and draw on their knowledge of landscapes and ecological processes to plan the work schedule.

Someone will still need to tell the robots what to do.

*****

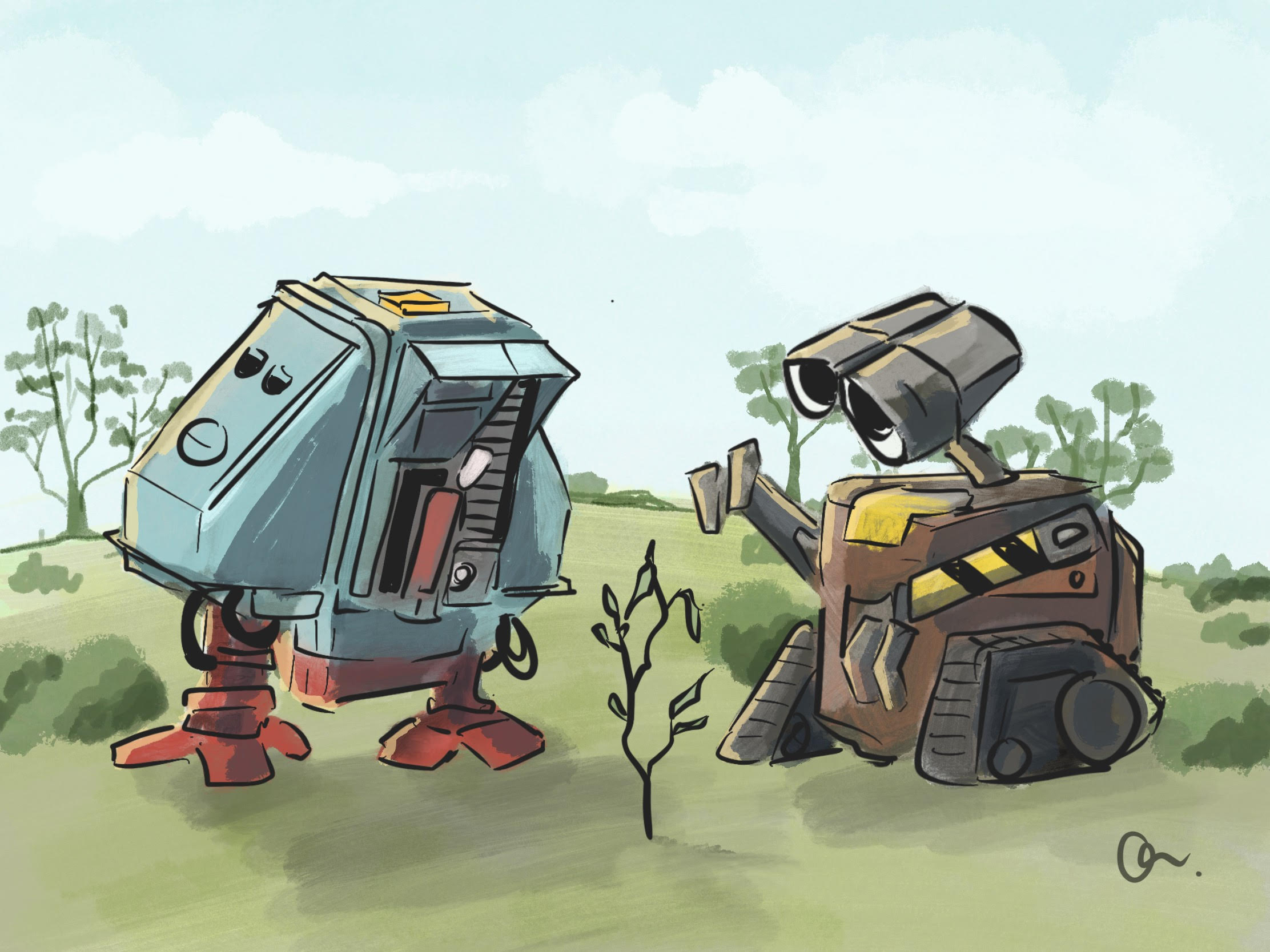

Text by David Mussared. Illustration by Alice Duigan Mussared

(dedicated to Dewey, 1972 & WALL-E, 2008)

Great topic to cover David! Thanks for posting!